#14 Chesterton's Fence

Let’s imagine you’ve inherited a beautiful property from a family relative, and you’re visiting it for the first time.

As you explore the land, you notice a hideous fence obstructing its beauty.

You feel that this fence is blocking the path and is the one thing preventing your property from looking perfect.

Naturally, your initial instinct might be to tear it down immediately.

However, here lies the problem — tearing down something without comprehending why it was built in the first place is a hasty decision.

Constructing fences takes time, money, effort and planning. 'By making decisions without adequate knowledge of why someone built it, we risk destroying something we don’t truly understand.

Chesterton’s fence advises us, “Do not remove a fence until you know why it was put up in the first place.”

Unless we’re aware of the underlying reasons, we do not have the power to make a rational decision regarding it.

It is so common for us to be so gripped by our own ideas and perspectives that we often forget to consider viewpoints that are beyond our comfort zones. is a narrow mindset which might cause us problems in the future.

It is important to acknowledge that the individuals who constructed the fence may have been just as intelligent as we assume ourselves to be, and that they might have logical reasons for their actions that we are just unaware of.

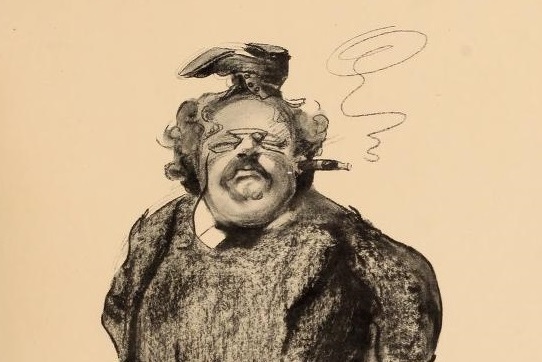

This principle was introduced by G. K. Chesterton, a renowned English author and journalist by a quotation in his 1929 book, The Thing, in the chapter titled, “The Drift from Domesticity”. He wrote:

“In the matter of reforming things, as distinct from deforming them, there is one plain and simple principle; a principle which will probably be called a paradox. There exists in such a case a certain institution or law; let us say, for the sake of simplicity, a fence or gate erected across a road. The more modern type of reformer goes gaily up to it and says, “I don’t see the use of this; let us clear it away.” To which the more intelligent type of reformer will do well to answer: “If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it.”

It is significant to note that Chesterton wasn’t discouraging or advocating against all forms of reforms. Instead, it highlights the need to be open to new ideas, adapt and find ways to solve problems, while fully understanding their effects on the existing system.

This principle is often used in defence of conservatism, which I think is a misuse of it. Change is necessary, though changing things purely for the sake of it isn’t intelligent and can be harmful at times. Furthermore, some things are meant to remain unchanged.

It is easier to demolish and remove things, but the real challenge lies in choosing if or what to replace them with. The key is to think from different perspectives while also examining the consequences as well as the consequences of those consequences in advance.

I hope this newsletter serves as a reminder that things may be more complex than they initially appear to us and that what we think of as arcane may be deliberate actions.